How to Navigate and Exit the Idea Maze with a (Good) Startup Idea

2025-01-11

In 2020 when we were at the beginning of our startup journey I had a conversation with Erik Goldman where he shared this process, which we used to start Column Tax. I'll be forever grateful for Erik's time, and I thought it worthwhile to capture Erik's wisdom permanently online so others could benefit as much as I have.

Intro

Navigating the early startup idea maze and finding a (good) startup idea to work on is incredibly tough. Having a process can help you a) find and validate a good startup idea and more importantly b) stay sane by feeling like you're making progress while doing it.

In this post, I'll explain a well-tested process for finding early Product<>Market Fit called "Hypothesis Sheets", why the process is useful, and how to follow it. This process works to validate startup ideas for venture-scale B2B companies. This process has led to many billions of dollars in market cap created. This post is geared toward starting a B2B company — if you're starting a B2C company2 I believe Hypothesis Sheets can help, but that's not my area of expertise — good luck 😂.

Starting a venture-backed company is never easy, but this process can help make the early days slightly more enjoyable.

The process boils down to 4 steps:

- Come up with a list of ideas/target customers

- Decide on a target idea/customer type to validate

- Validate that idea/customer type using Hypothesis Sheets

- Continue de-risking or move on to the next idea/customer type

Let's go into detail on each of these:

The core idea: startups are a series of hypotheses

Companies are a series of hypotheses. Similar to the scientific method, successful founders are able to continually set the right hypotheses and prove/disprove them to move the business forward.

An untrue hypothesis that the business relies on represents a risk. The process of moving a company forward is the process of de-risking the company's biggest risks.

In the beginning, the core risk is "what problem should we tackle?" — while later a risk might be, for example, "can we sell to larger enterprise customers?"

As a founder, you should always be de-risking the business's top risks. But this is especially important to be doing in the very early days. You should be more rigorous and analytical than you expect on day 0. The Hypothesis Sheets method helps bring rigor to this very ambiguous phase.

Finding Product<>Market Fit

There are two main checkpoints for a startup: 1) finding PMF and 2) scaling it.

You must internalize that PMF is tough and random to find. And the optimal strategy to find PMF is not making just one attempt: the more "darts" you can throw to try to find PMF, the better. VCs have an inherent "dartboard" built into their business model, so you can't necessarily trust their advice on this topic :).

Throwing a lot of darts: have a formal process

So how do you throw a lot of darts? Start by coming up with a list of ideas/customer types that you'll validate. Decide on which idea/customer type you're going to validate and for how long (I recommend working in 1 week sprints).

Then, don't spend more time than you need to on any single attempt. Make sure you move on at the right time. Have a set threshold you are trying to reach, and then de-risk as quickly as possible (using the process below) to decide (using the framework below) if you want to work on this idea or move on to the next one.

Overall, you should have a formal process for this idea maze phase. 80% of the reason to have a process is to stop yourself from going insane because progress is so nonlinear-feeling during pre-PMF startups. The Hypothesis Sheets method helps by providing structure so you can more easily track the progress you're making (even if that progress is proving a hypothesis false and throwing away an idea).

The process: Hypothesis Sheets

The formal method for validating each idea is called "Hypothesis Sheets".

Here's how it works:

- Write down everything you believe to be true about your customer (and why you think it's true).

a. Do this no matter what: don't start with a blank sheet. Start by writing down what you actually think even though it's probably wrong. Write something down even if you think you know nothing at all.

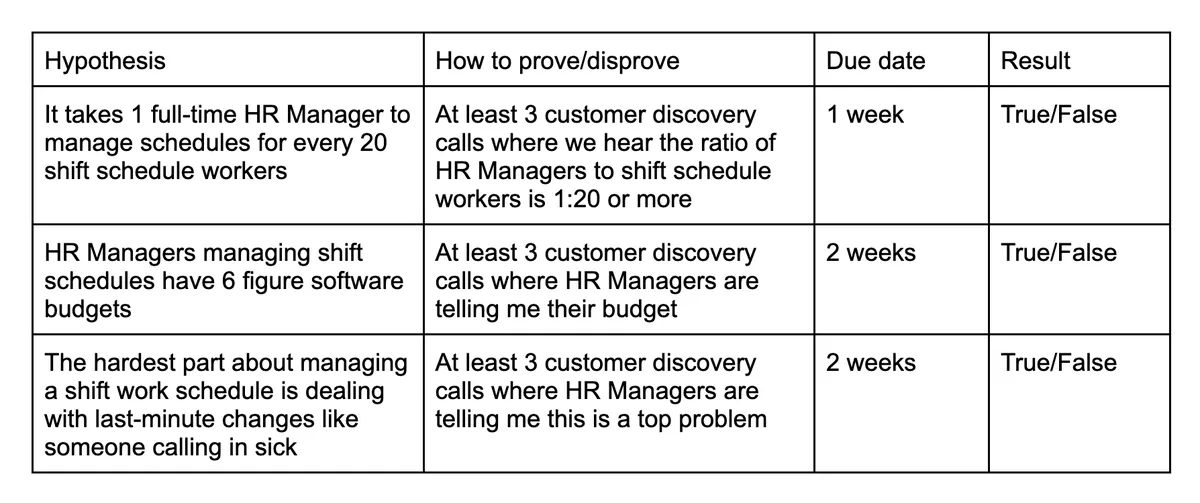

b. For example, if I were starting a Hypothesis Sheet for HR Managers at shift work companies, I might start by writing down a few hypotheses:

i. "HR Managers have a hard time managing their workers shift schedules"

ii. "HR Managers managing shift schedules have 6 figure software budgets"

iii. "The hardest part about managing a shift work schedule is dealing with last-minute changes like someone calling in sick"

2. Next, stack rank which hypotheses are most important and prove each item on your list true or false. And add new hypotheses as you're going.

a. Be very rigorous/honest about how to prove each hypothesis.

b. For example, for a hypothesis about a customer's workflow, you may be able to prove/disprove it by doing customer discovery calls. E.g. we can learn what the hardest part of an HR Manager managing a shift work schedule is by talking to people who do that job directly and asking them about their current workflow.

c. But for other hypotheses, e.g. will someone buy [a product], the only way to prove/disprove it may be to put a checkout screen in front of a user and see how many people enter their credit card number and click "buy". Asking your customers (or worse, your friends) if they would buy your product simply won't cut it: there's a huge difference between someone saying they will buy something and them actually paying money for that thing.

3. Eventually, progress on proving/disproving/adding hypotheses to your list will slow.

a. One sign this is happening is that you keep having the same customer discovery convo over and over: a good rule of thumb is that if you hear the same thing 3 times in customer discovery convos, you can likely move on to the next hypothesis.

4. Then, look at your Hypothesis Sheet — and you'll Just Know something to build that people will want.

a. If you hit a wall: you either have the perfect product to build or you're wrong about one of your hypotheses.

Here's an example initial Hypothesis Sheet for my imaginary company selling to HR Managers managing shift work schedules:

As we prove/disprove each hypothesis, we can mark it True/False in the last column, as well as add/update hypotheses as we're talking to more people.

Here's a template you can use to start your Hypotheses Sheets: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/16F6SxCeeTuFtnR-qieQw_c8oai1Fih1jKUrCUy-MLA8/copy

Caveat: you should throw away an idea/customer type/market when:

- you know the product to build, but it's not and won't become VC-backable scale13

- you are completely stumped about what to build based on your proven hypotheses

- you know what to build, but you would have no real moat (for example, users just want a better design, e.g. Mailbox)

Remember, arbitrage opportunities close quickly in business! So it's important to move quickly. I recommend working in 1 week sprints during this process. Set a goal for the sprint (i.e. which hypotheses you are going to prove/disprove this week and how) and then check in at the end of the time period to decide to continue learning about this customer or switch to a new one.

How to run customer discovery calls

One of the most common ways you will prove or disprove hypotheses about your target customer during this phase is by doing customer discovery calls.

The worst question you can ask during a customer discovery call is "what are your problems?" — don't do this and expect to get a real answer. If they already knew the answer, they would have solved it by now! So the answers to that question are always bad. Don't literally take what customers are saying at face-value. When someone says their biggest problem is X (e.g. hiring), their real problem is actually probably Y or Z (e.g. they have a non-inspiring mission).

People cannot at all speak about the future ("where is your industry heading?"). And people are surprisingly bad at abstract thinking ("what are your problems?", "where are you spending the most money?"). But customers are fantastic at telling you concrete facts about the past/present ("would you be comfortable sharing your calendar with me?", "can I see your software budget for this year?", etc.)

The better process for customer discovery

Ideally, you'll do enough customer discovery such that you can build a model of your customer in your mind so you can simulate them and then do "customer discovery" internally inside your company. This means understanding your customers well-enough so you know their real problems, not the ones they say they have.

It's common for founders to have an "industry" they're looking into. But I recommend switching how you think about this phase of the process to thinking about "customers" instead. E.g. instead of thinking about starting a company in "Shift scheduling management", instead learn about what "HR Managers" or "Shift Workers" need. Presumably these specific customers have problems they need solving (and are willing to pay to have solved).

For more advice on this, read the book The Mom Test (this is my bible and I highly recommend it).

A couple of specific customer discovery hacks:

- At the end of the call, ask: "is there anyone else in your field you respect?"

- And then live on the call (it's uncomfortable to do, but it works): "would you be open to introducing us?"

- Also, you can tell them "I'm building this Hypothesis Sheet that I'll send you after" — which can provide value to the person and make talking to you seem more worthwhile.

Conclusion: this is not necessarily a fun time :)

A reminder for folks in the idea maze: when you talk to founders further along (including me!) we will sometimes look back at this idea stage as "fun" and that the world "was our oyster". But remember that you're likely talking to folks who made it out of the idea stage. For every founder who made it out, I know half a dozen who spent months to years in the idea maze and never made it out. In other words, read this post with a healthy grain of this:

Survivorship-bias Be careful of Survivorship Bias: you're only hearing advice from people (like me!) who survived the startup idea maze, not those who never made it out.

Finding PMF is hard for everyone. There's something magical about being able to get to the point where your problems are totally different from "what should I build?" — good luck!

If you have questions about this essay or think I got something wrong, send me a message — I read & respond to every DM/email I get.

Thank you to Erik Goldman, Hannah Squier, Julian Ozen, Oliver Gilan, Achyut Joshi, Nathan Lord, Nadia Eldeib, Varun Khurana, Idan Beck, Aditya Agarwal, and Andrew Rea for reading drafts of this essay.

- There are lots of reasons startups are tough. But two of the top reasons in the very early days are: limited time/runway and limited motivation. Long feedback loops are slow and demoralizing. The goal of Hypothesis Sheets is to shorten feedback loops and therefore (in Erik's words) make starting a startup more tolerable in the early days.

- Consumer companies can be like trying to find "lightning in a bottle". It takes a special type of founder — who is willing to search for lightning to strike — to start a B2C company. It's still likely that a structured process like Hypothesis Sheets can help: the techniques you'll use to validate hypotheses are often different, but the philosophy is the same.

- If something is going to work, you should be getting increasing signals of PMF over time. At some point culminating in "undeniable PMF". But that's a spectrum and not unilaterally consistent, even in B2B companies. The point of this post isn't to debate the definition of PMF, but to help you exit the idea maze.

- There's one caveat to this advice: when you eventually begin recruiting employees, you can't say that you found your company idea by throwing 100 darts. People want to join companies with what feels like preordained certainty, so companies make up founding myths to help make recruiting easier. As an example, the Dropbox thumbdrive story is literally made up. And Blockbuster sued Netflix because Netflix's founding story about Reed Hasting's Blockbuster late fee was totally made up! Now that's a good founding story!

- The topic of coming up with a list of startup ideas is a topic for another post 😅 — but the quick version is there's a list of prompts you can ask yourself, e.g. "what do you believe that others don't realize yet?", "what do rich people have access to that others don't yet?", and "what are you uniquely good at?". If you're interested in me writing the post on generating startup ideas, let me know!

- Deciding on which idea to work on next is also a topic for another post 😅 — again, let me know if you'd be interested in reading this post.

- There is a strong emphasis on "than you need to" — I encourage you to literally brainstorm every possible way to validate something and then pick the cheapest one to do. One thing that's hard for some folks to understand is that if you're SpaceX, it might take five years to run your test. Don't pick something that can be done in a month but is insufficient to prove/disprove your hypothesis. The goal of a founder is to keep asking, "could we validate this with a cheaper strategy?" over and over — that's most of the job of a founder, even as the company scales.

- Whatever is in your head will either end up on the Hypothesis Sheet or just silently and incorrectly baked into your product: the Hypothesis Sheet is a much better place!

- A common follow up question is "how do I know which hypothesis is the highest risk?" and the answer is: "don't think too hard about quantifying risk with a framework here, just do a gut check and roughly sort". You'll probably be close to right.

- Erik calls this "surprise factor". Surprise factor is when you ask, "and that must have been really bad, right?" and the customer says, "no, it was great" or something equivalently surprising. Surprise indicates that your Hypothesis Sheet is broken and needs to be rearranged to better capture the state of the world. If you build a product based on a Hypothesis Sheet with surprise factor remaining, you will be surprised when no one wants your thing! Erik encourages founders to track surprise factor qualitatively but explicitly with each validation step. Eventually, surprise will die down and your model is now aligned with the world. You can now iterate on ideas without leaving your house because you have the correct world model!

- Another heuristic is to track overall surprise. When things are slowing down, you can even challenge yourself to ignore the sheet and just try to find surprise (aka where the model breaks) in a conversation. If you can't find it, you're good to move on.

- Or not! Many Hypothesis Sheets end with a conclusion that there's nothing there. As long as you ran the process, you can feel good about moving on to something else. When founders are discouraged at the end of a Hypothesis Sheet, Erik will often encourage them to write a blog post about what they learned: this is a much more tangible artifact of progress than just silently pivoting.

- Based on your analysis of if the market is big enough to support a venture-scale startup. How to do this is also probably the makings of another post! There's also one caveat: and you don't have a specific hypothesis about why the market will grow into a venture-scale.Many great businesses started as niches (e.g. personal computing) but there was a single hypothesis (that could be rejected) about why it wouldn't be that way forever. When Erik did Vanta's seed round, the question they'd ask is: do you think there will be more regulation on tech companies in the future, or less? Vanta was a bet on "more". It could have been less! That's what betting is. But being specific about what the bet is that the market will be much bigger in the future is much easier to understand than generalities.

- The Efficient-market hypothesis is probably not true! Good startup ideas don't last forever.

- How to find and schedule customer discovery calls is a topic for another post 😅 — there are lots of micro tactics to use to get folks on the phone/Zoom. The quick version: do 10x more than you think you need to to get in touch with people.

- The emphasis here is, "don't learn about customers' problems, learn about customers". Sitting down and asking someone, "what are your problems" is trying to start the race at the finish line (and also won't work). Instead, try asking: "what's your background? how did you get into this line of work?" / "can you go through your calendar and tell me what you did this week? what did you do in (meeting)? is that related to a goal your team has this year?" / "what do you enjoy about your job? what do you hate about it?" / etc. Do that for a few hours and you won't need someone to tell you their problems, you'll have enough information to describe them in your own words. Often, you'll surprise a customer by summarizing what you learned and it will be a perspective they haven't thought about in their own work. That's because they don't interview, e.g., tax accountants for 30 hours about their lives; instead they spend time reading the tax code and getting things done. You actually have unique insights on them that they don't have time or resourcing to compile themselves!